Lesbians and Cycling: an Illustrated History

Last month I ran a posting featuring the group photograph below. I suggested that one of the men pictured looked rather feminine and, perhaps, was a woman impersonating a man.

A 19th Century woman muscling in on a man’s world by wearing a fake moustache*? Sounds far-fetched but then I stumbled upon this 1890 picture of a woman photographed next to a highwheeler. The woman sports a fake ‘tache and is dressed as a man.

The woman is Frances Benjamin Johnston of Washington, D.C. She was a professional photographer and this photo is classed as a self-portrait. Her extended foot is probably pressing a remote switch, taking the shot.

The Washington Times, of April 21st 1895, said:

“Miss Frances Benjamin Johnston is the only lady in the business of photography in the city, and in her skillful hands it has become an art that rivals the geniuses of the old world.”

Miss Johnston took photographic portraits of presidents (she was the official White House photographer for a time) and socialites. She also photographed leading womens’ rights advocate Susan B Anthony.

Famously, in 1896, Ms Anthony told the New York World’s Nellie Bly:

“Let me tell you what I think of bicycling. I think it has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world. It gives women a feeling of freedom and self-reliance. I stand and rejoice every time I see a woman ride by on a wheel…the picture of free, untrammelled womanhood.”

An 1891 article in Outing asked “where shall [women] ride?”:

“The smiling countryside holds out arms of welcome to her, the shaded grassy road, the smooth steep incline, the bumping corduroy by-ways, the canal towpaths, the lakeside drives and the stubborn stiff hill to be climbed.”

Women on bicycles broadened their horizons beyond the neighbourhoods in which they lived. Cycle historian Jim McGurn has said that in the Edwardian era cycling extended people’s geographical reach (better roads would help in this respect), enabling couplings from outside a confined area. Cycling helped expand the gene pool, he posited. But cycling was also a vehicle, as it were, for couplings that wouldn’t result in offspring. Same-sex relationships have a long history and cycling had its part to play.

Johnston was a lesbian, openly living with her partner, Mattie Edwards Hewitt (also a photographer), and was one of the key members of the feminist New Woman movement.

The “New Woman” embraced the bicycle as a means of emancipation. On a bicycle, a woman was equal to a man.

On their “wheels” – the 19th Century American term for bicycles – women discovered freedom of movement, helped in part by the new, less restrictive clothing popularised by the New Woman movement: bloomers.

By dressing as a man in her 1890 self-portrait, Johnston was being deliberately provocative, challenging the status quo. The use of an Ordinary as a prop is telling. These were difficult to ride, even for athletic men, and the late 1890s bicycle craze came about because of the increase in popularity of Safety bicycles. By 1890, Ordinaries were being ridden less and less but were still equated with male athleticism. This particular Ordinary doesn’t look too big for Johnston and is very likely to be her machine but by 1890 she also, presumably, had a Safety bicycle.

Many of her ‘New Women’ contemporaries rode bicycles. The poster above was in her studio. It’s by Charles Dana Gibson from the June 1895 issue of Scribner’s magazine and shows a ‘New Woman’ awheel, wearing a blouse with voluminous leg-of-mutton sleeves tucked into the waist of her bloomers.

Not all of the female cyclists of the 1890s were lesbians, far from it. But the worlds of feminism and lesbianism were linked (as were the worlds of photography and bicycling), and cycling couldn’t help but be part and parcel of the scene. One of the key women’s cycling instruction manuals of the age was Bicycling for Ladies by Maria Ward.

In the preface to her 1896 book, Ward wrote:

“I have found that in bicycling, as in other sports essayed by them, women and girls bring upon themselves censure from many sources. I have also found that this censure, though almost invariably deserved, is called forth not so much by what they do as the way they do it.”

There were copious photographs in Bicycling for Ladies, many of them of gymnast Daisy Elliot, who demonstrated cycling techniques such as how to mount, dismount, and carry a bicycle. The photos of Elliot were taken by Alice Austen, a friend of Ward’s, and a key figure in lesbian history. Ward photographed “the larky life” of the gay nineties (no, not yet that kind of gay), such as her friends playing tennis, or bicycling. And as her friends were mostly lady friends (“she lived an unconventional lifestyle [and] was never to marry”, says the video at Austen’s home on Staten Island, now a National Historic Landmark) she took photographs of them cycling. But, in many of these photographs, the women dress as men. Either Austen got the idea from Johnston, or Johnston got the idea from Austen. Either way, in the 1890s, the bicycle was a revolutionary thing, transforming in so many ways.

NB Cross dressing wasn’t common in Victorian times but it happened, in America as well as Britain, as demonstrated by this key-word search on VictorianLondon.org.

“At Liverpool a woman who has for nine years disguised her sex, dressing in male attire, and earning a living as a cabdriver, is now in custody for having stolen some butcher’s meat.” The Graphic, February 1875

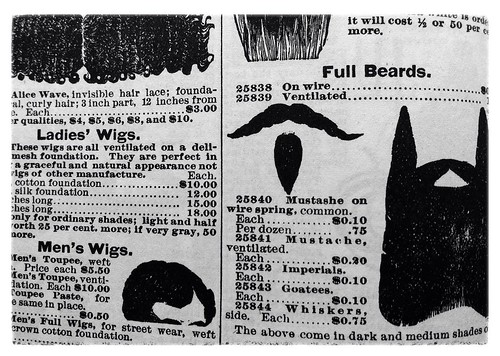

* Access to high-quality real-hair goatees, moustaches and full beards was easy in the 1890s. The Sears Roebuck & Co catalogue of 1897 even sold mutton-chop whiskers, and for just 75 cents.

Pingback: Clickity Click! ~ The Karina Dresses Blog